The Human Side of Mobile Crisis Care: A Philosophical Perspective

Guest Column by Sarah M. Gorman Ph.D for the December 17 issue of the AMSA Weekly Newsletter

“All of you are perfect, and you could use a little improvement.” - Soto Zen Priest, Suzuki Roshi

Hello readers,

I was asked to write this article about mobile crisis as someone who uses psy-services, and as someone who is a philosopher, I also write this as someone who until recently was actively experiencing suicidal ideation and psychosis. I have experienced the mental health system from multiple angles—as a service user, as a child of service users, a person with lived experience of suicidal ideation and psychosis, and a third-generation person with schizophrenia, so I bring a unique perspective to the discussion of mobile crisis care. Until my recent stabilization, I was more likely to have crisis services called for me than to call them myself. I call 988 carceral care, and when I advise suicidal people I tell them that certain suicide hotlines might call the cops on you and others won’t.

Perceiving the Person First

Seeing people as risks [to themselves or others] - seeing people as threats - seeing people as a means - seeing people as victims - seeing people as criminals - seeing people as deranged - seeing people as [diagnosis] - seeing people as addicts. These are all ways of seeing that you have been trained to do. This training is what brought you here. But in the moment of mobile crisis care, you should forget it all.

Each of these titles or states get in the way of seeing people as persons, as ends in themselves, with faces, desires, fears, a history, a future, a current state of capability to experience and to suffer. At the least. Many you come into contact with will also be able to understand. To speak. To trust. To listen. To have insight.

You might know they’re a person but when you see someone as one of the above states or conditions, you’re missing out on their humanity as something that you both share in common. Your commonest element is dignity, the spark you feel when locking eyes. If you look them in the eyes and see nothing there, there’s something wrong with you not with them. Get checked out. Perhaps you have compassion fatigue.

The Duck-Rabbit Principle

What do you see in the image below? Duck or rabbit? I’m not trying to make a point about your unique way of viewing and what that means for you, or even to make a point about how there are two kinds of people in this world–people who see a duck versus people who see a rabbit. This is the duckrabbit:

[Perceived from left to right: a duck with a bill facing left. Perceived from right to left: a rabbit facing right. The duckrabbit illusion drawing.]

The same way you can only see the duck or the rabbit while simultaneously knowing it is a duckrabbit, seeing as persons paired with any of the above states or disorders precludes you from simultaneously seeing people as human persons. You have to make the conscious switch from one way of seeing (the clinical or diagnostic way), to another, more human way.

Mindfulness in Crisis Work

Mindfulness therefore, is something crucial for those who are doing mobile crisis work. You need to become aware of yourself as aware of something and as making certain professional and personal judgments any number of which preclude you from seeing the human person in front of you as a person capable of suffering. Cultivate mindfulness, notice yourself judging or categorizing persons. Then make the active choice to instead see this person before you as a person, perhaps on their worst day.

Understanding Suicidality

In other words, check your bias before you approach someone who is suicidal: fearful for their lives. Suicidality is not just to wish yourself dead or to want to kill yourself, it’s to fear for the continuation of your life to such an extent that it begins to impair your ability to move forward. It’s when the death drive wins out over generative or sustaining libidinal or life drives. It might mean stasis for some, depression, agitation, hopelessness, mania, or heightened anxiety, fearfulness, and/or self harm. Substances can make things worse.

[A Note on Deescalation: sometimes people yell. Sometimes they yell at the voices in their head or someone they’re arguing with whom you might not be able to hear or sometimes they just need to annunciate out loud. Just because someone is agitated doesn’t mean that you have to subdue them.]

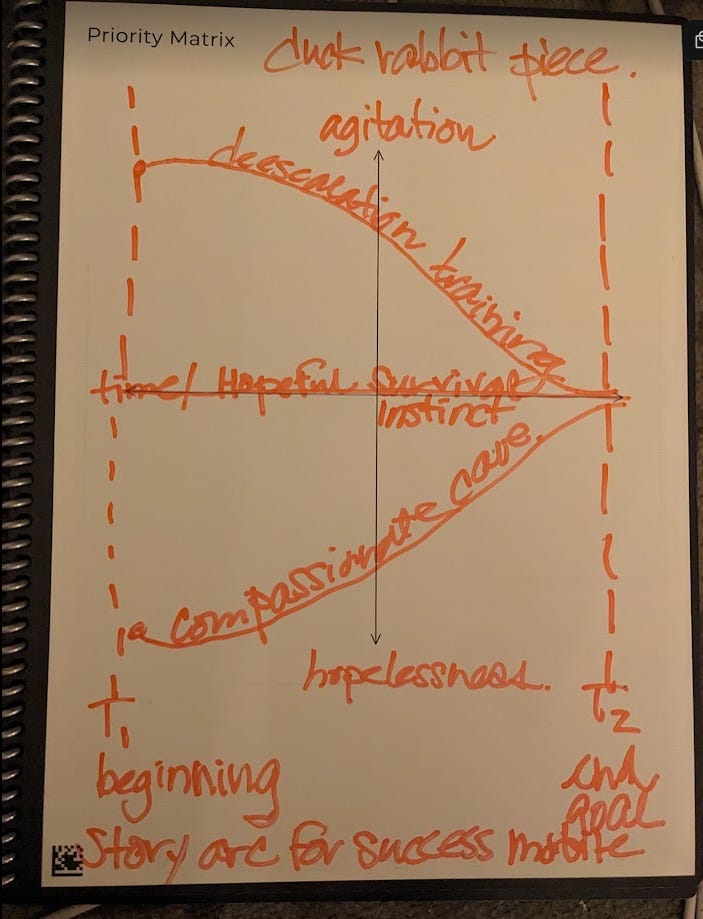

I made you a chart. I fancy myself a fiction writer right now as well as a philosopher. Here is the proposed story arc for a successful mobile crisis services call:

The Arc of Crisis Care

[Image description in the text that follows, two simple story arc drawings on an XY axis in red handwriting]

Time T1 is the beginning of the call. When you begin by answering to the person you’re trying to help. Time T2 is the end of the call. It’s your goal. The Y-axis is the feeling axis. It stretches from agitated through hopelessness, the two extremes of feeling you’ll likely encounter persons experiencing in mobile crisis situations. Line A labeled deescalation training is mirrored across the equilibrium X-axis by line B which is labeled compassionate care. Deescalation training and compassionate care are the two tools you’ll be using mainly while working in mobile crisis.

Your deescalation training will serve to defuse tension and bring the person down to a comfortable equilibrium of looking towards the future. Compassion reaches out towards the other with an extended hand, whereas empathy merely means feeling-with. Compassionate care can get the individual from low on the hopelessness scale, to more of an equilibrium ideally to the “hopeful/survival instinct” equilibrium of the X-axis. Your deescalation training will be most helpful if you’re encountering someone who’s agitated, whether that is because of mania, or fearfulness, “paranoia,” or substances.

Your Aim Is To Earn Trust

None of the above “causes" should be thought about in the moment of caring. Remember, you can only see the duck or the rabbit: one at a time. You must consciously choose to release those judgments and see the person in front of you. Release “seeing as” anything but persons in the moment of mobile crisis care. You should approach individuals with curiosity and open mindedness. Your aim is to earn trust.

Keep in mind that generally, people who come in contact with you are seeing you on their worst day. Having mental health stuff going on by itself is scary. To be in public whilst also having mental health stuff going on is extra scary. Lead with kindness and respect for that, rather than with force.

I repeat, just because someone is agitated does not mean they need to be subdued. You have the most powerful anti-violence instrument with you always: it’s the human voice. Try with a greeting first “Hello. I’m X” In other words, introduce yourself to the person you’re trying to care for.

I have never done crisis work but I grew up in a schizophrenic family. I’ve witnessed many mental health crises. I’ve been in my own crises as well. I once was with a friend walking down the street in Nashville. I said hi to a man who was yelling at no one in particular. I looked over at my friend to say “he was having a hard time.” My friend commented that she reacted with fear because she thought he was a risk to us. She noted the difference in our ways of engaging. I did so with curiosity and open mindedness.

As a third generation schizophrenic, some wisdom my father passed down to me was when you’re having a hard time, to speak with someone who you can trust to understand. He learned this from his schizophrenic mom. I would like to add that a smile goes a long way towards making someone who’s having a hard time feel comfortable.

Building Trust Through Understanding and Trauma Stewardship

As someone whose job is to deescalate crises and offer compassionate care, you need to earn trust. Your badge and your credentials, while impressive, might make you less relatable. You need to look these human persons having a hard time in the eye and you need to muster the compassion to reach out to them in their messy, difficult, sometimes painful reality. You want to, through your deescalation training, bring them down from agitated to an equilibrium of hopeful or looking forward or you want to–with compassionate care–bring them up to an emotional equilibrium oriented towards the future.

The last tool I hope to give you in this message is Laura van Dernoot Lipsky and Connie Burk’s idea of trauma stewardship. In the mobile crisis sphere, you should always remember the sacredness of being called to help. Your vocation is to be a trauma steward. To be mindful of your prejudgments, and then to choose to act with the humanity of the person before you in mind. To, through deescalation or compassionate care, connect with the human being in front of you on a human level. To be curious about them and their struggles. To reach out a hand and help them see a future for themselves.

Sustainability as a Principle

As a trauma steward, you must also be acting with a principle of sustainability in mind. Your use of coercion or force will, regardless of your intention while using it, color the person’s future perceptions of accessing services–all services. If you lead with force, you automatically undermine the mandate of trust building and you undermine that person’s perceptions of service access in the future. If you lead with force you do not act with sustainability in mind.

We want you to act in such a way that invites people to come back and ask for further help. Suicidality can be persistent and recurrent. Sustainability is a mindset. You want people to feel welcome to interact with services. You don’t want to give coercive care because the next time the person is experiencing a crisis, they won’t ask for help at all, or they’ll wait til their circumstances reach a further crisis point to ask for help. Sustainability should be the mindset, try and make future engagement easier by not using force this time.

Sustainability Means Caring for Yourself Outside of Work

Trauma stewardship also recalls the toll of experiencing trauma second handedly. You are at risk in your line of work. So you should read the trauma stewardship book in its entirety, and practice some of the exercises. Sustainability is also something that applies to your own self care and coping mechanisms. Trauma stewardship recognizes the toll that being in the helping professions has on the helpers: on you. In the interest of sustainability, the sustainability of your life and your job, you need to invest in your own self care. Mindfulness is crucial for this process too.

How did you feel when that man ravaged his veins in front of your face on the coffee shop patio? Why did he use a broken beer bottle to open his veins? You need to pay attention to your own reaction to second hand trauma. You need to mindfully process these experiences. It was hard to see, and you were repulsed. Recoiling in horror. You need to feel that horror so it doesn’t gain a life of its own somewhere in your body.

Sustainable practices take care of you first. The less you have to use force at your job the better, right? Trauma stewardship maintains that “when we lose compassion, our capacities to think and to feel begin to constrict.” (van Dernoot Lipsky and Burk) You have to be able to think and to feel to do your job. You must therefore keep sustainability in mind and figure out a way to systematically care for yourself, working towards the maintenance of your body, spirit, and mind. You need to make caring for you a priority while you keep caring for others.

Final Thoughts

Crisis work requires a delicate balance of professional skill and human connection. Your goal is to help people move from crisis to hope, whether that means de-escalating agitation or lifting someone from hopelessness. Lead with kindness, approach with curiosity, and remember that the person before you is having one of their hardest days.

The wisdom passed down through generations of my family holds true: connection and understanding are powerful medicines. As crisis workers, your role is to embody that understanding and help guide people toward hope. Towards perceiving – and not fearing – a tomorrow for themselves.

By Sarah Gorman, Ph.D. Contact at dr.sarah.m.gorman @ gmail.com